During the summer and autumn of 1884, Britain saw perhaps the largest series of political demonstrations in its history. Thousands of processions and public meetings took place across the country in protest at the attempt by the Tory-dominated House of Lords to block a reform bill which would enfranchise around two million mainly working-class men. There were at least 20 meetings and demonstrations in Lancashire, the two largest being in Manchester and on the moors above Rawtenstall, where 15000 people turned out on 4th October to make their voices heard.

The 1884 Franchise Demonstrations in the Lancaster Area

Posted by Dr. Mark Nixon

Obverse of a commemorative medallion by Maher & Son of Birmingham. In front of the lion are the words ‘Gladstone and the Franchise for Two Millions. 1884’, and around the edge ‘The Constitution in all its Fullness for the People of the United Kingdom’. The medallion has been holed so that it can be attached to a pin, rosette or ribbon to be worn.

Under the Second Reform Act of 1867, a man had to be richer if he lived in a ‘county constituency’ than a man living in one of the towns and cities that enjoyed ‘borough constituency’ status to have the vote.

In early 1884, Gladstone’s government had introduced to the Commons a bill to equalise the franchise rules. The Conservatives in the House of Lords, fearful of the loss of many seats they considered natural Tory territory in the face of new votes from agricultural workers, coalminers and other trades, refused to pass it without a redistribution bill altering constituency boundaries to protect their interests.

The reaction from Liberals, Radicals, and many of those likely to gain the vote from the bill was one of anger. On 5th July, the Radical-Liberal Lancaster Guardian published a leader column arguing that, should the Lords continue to try and block the bill, it ‘will have raised against itself the active hostility of the nation’. The previous day, even the moderate Lancaster Observer had worried about ‘the possibility of a coming fury beyond anything known to 1832 and 1867’, two previous periods of reform agitation.

'Our legislators should be chosen by the people from the people.'

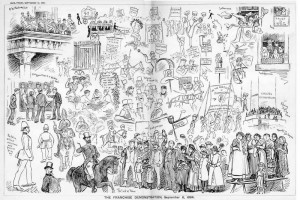

Drawings of the franchise demonstration at Glasgow by the news artist ‘Twym’ [AS Boyd], published in the magazine Quiz. The street decorations, banners and models shown include many images of Gladstone, a ‘death bed for the Lords’ and two pigeons in a cage with the motto ‘We Want Our Liberty’. Composite image by Kevin Kerrigan.

The Lancaster Reform Club propose ‘hearty approval’ of Gladstone’s Bill to equalise the franchise rules

Lancaster – which had been disfranchised in 1868 as a parliamentary borough due to a history of corruption – held its own meeting on 30th July, in the Palatine Hall. It had been organised by the Reform Club, and their president, James Thomson, chaired the proceedings. In his speech, Thomson suggested that 40,000 men in north Lancashire alone would gain the vote should the bill pass. He was followed by the Rev. J Freeston of Manchester, and then Mr TBP Ford of Bentham, a Quaker industrialist, who proposed the first resolution expressing ‘hearty approval’ of the bill. It was passed amongst loud cheers. A second resolution, complaining of the ‘abuse of power and privilege’ by the Lords was proposed by Mr J Sellers of Preston, and seconded by the Rev. D Davis. In support, the Rev. HW Smith delivered ‘a very forcible and eloquent speech’ in which he spoke strongly against the institution of the House of Lords itself.

The Lancaster and Carnforth meetings approve an amendment and a resolution to abolish the power of the House of Lords

At this point, one James Crookall rose from the audience and asked to put forward an amendment to the second resolution. After some commotion, he was allowed to address the meeting from the platform, where he complained at the ‘weak and halting and utterly inadequate’ resolution, spoke of his interests as a non-elector – unlike the men with votes who had spoken so far – and against the principle of hereditary power, and moved ‘…that the power of the House of Lords to reject measures approved by the elected representatives of the nation ought to be abolished.’

The demonstrations – huge, noisy, and radical – had forced the hand of the governing elites. The men and women of Lancaster and Carnforth had played their part in developing democracy in Britain.

Reverse of the Maher medallion with the words ‘Our Queen Our Country and Our Rights’ around the edge, ‘Justice For All’ on the scroll above the crown, and ‘Peace. Law. Order’ below.

On this, Crookall was in accordance with the views expressed at many of the demonstrations being held around the country. Although ostensibly about an extension of the franchise, it appears that the majority of working-class Liberals and Radicals present at the demonstrations wished for something more: the ‘mending or the ending’ of the House of Lords. Many banners have survived from the events of 1884, giving an insight into the views of the demonstrators, which counter the official histories and contemporary newspaper reports, with mottoes such as ‘Our Legislators Should Be Chosen By The People From The People’.

The Lancaster Guardian’s reporter noted that the amendment was well received in the hall, and the Rev. Smith proposed it be put to the meeting not as an amendment but as a third resolution: it was passed ‘with hearty cheering’.

On 9th August, local Conservatives held a much smaller meeting in Lancaster in support of the Lords. On the same day, another meeting in support of franchise extension was held, this time in the yard of the Station Hotel, Carnforth. Many of the local great and good who had been on the Lancaster platform were on the Carnforth platform, joined now by James Crookall. On the previous Saturday, he had led a Lancaster deputation to the massive demonstration held in Birmingham, where the senior MP was John Bright of Rochdale, who was hugely popular for his support for franchise extension.

Promotion to the platform had not dimmed Crookall’s opinions nor his language. Two million ‘capable and trustworthy’ men had been denied their rights by ‘300 irresponsible and hereditary lordlings’. He proposed that the Lords be ‘brought into harmony with the principles of popular and representative government’, arguing that they were beyond reform and needed to be abolished. ‘This,’ he said, ‘was the question that was now to be decided’. The resolution was passed, just one person voting against.

Throughout the country, opinion hardened. The Tory press warned of a ‘red tide enveloping all institutions’, and reported on the actions of ‘dynamitards’ and ‘nihilists’ on the continent. ‘Respectable’ Liberal voices expressed their concerns: the Lancaster Observer’s leader column of 17 Oct, entitled ‘Armed Politics’, reflecting on a major riot at Birmingham and warning of ‘Civil War’, inveighed against ‘ultra-Radical advocates’, writing that ‘Deep down in the nature of the lower classes there is a savagery that is as formidable and as resistless as that of any African’. The language of the demonstrators had gone well beyond anything the Liberal party could countenance, and in the many speeches he gave in September and early October, Gladstone told his audiences that the errors of the Lords was no reason to abolish the institution. He was booed for his trouble.

At hastily-arranged meetings between the Liberal and Tory leaders in late October, a compromise was found and the bill was passed. Fearful of something far worse – a revolutionary ending of hereditary privilege in Parliament – the Tories accepted two million more voters, and the Liberals agreed to a redistribution of seats which, while not entirely to the benefit of the Tories, did accede to most of their demands for a clearer separation of rural and urban districts. The demonstrations – huge, noisy, and radical – had forced the hand of the governing elites. The men and women of Lancaster and Carnforth had played their part in developing democracy in Britain.