George Harney was part of the critical trial of Chartists at Lancaster Castle in 1843. Why was a man from Deptford charged in Lancaster, and what success did his campaign have?

A Story of the Chartists movement and Lancaster

Posted by Tyler Bryce

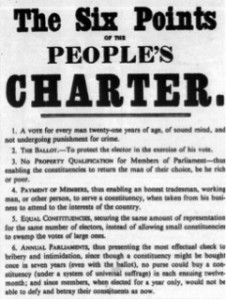

The Essentials of Chartism

Chartism is, perhaps, the first political protests made up mostly of the working classes. The initial trigger for the movement came in 1832 when Parliament passed the ‘1832 Reform Act’ which effectively meant that a larger percent of the adult male of the population1 of the UK at the time could vote. The figure grew only to 18% of the total population of adult males, leading to dissatisfaction (2).Chartists emerged around 1836 and the movement’s activities peaked between 1838 and 1848. The overall aim of the Chartists was to gain political rights and influence for the working class. The political rights were only to be given to men, as women’s suffrage hadn’t been given any serious thought yet. The Chartist movement was primarily set up by William Lovett a Cornish Cabinetmaker who started the “London Working Men’s Association” with the aim of seeking “by every legal means to place all classes of society in possession of their equal, political, and social rights.’. He produced ‘The People’s Charter’ which gave the main six goals of Chartists, these aims were(3) :

- A vote for all men (over 21)

- A secret ballot

- Payments for MPs

- No property qualifications to become an MP

- Electoral districts of equal size

- Annual elections for Parliament

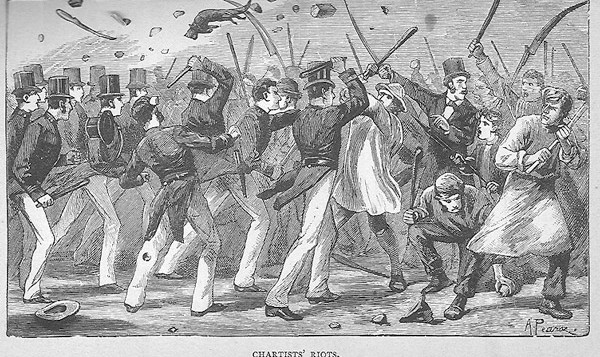

59 men on trial at Lancaster - charged in what the Chartists dubbed the ‘monster indictment’

Political Context

At this time Queen Victoria was the reigning Monarch with the Whig representative Lord Melbourne as the Prime Minister. The Whig political party(5) was a moderately conservative party who were against absolute rule. The 1832 Reform Act (mentioned above) was their signature measure while in government and they also abolished slavery in that same year. They were notable for being sympathetic towards nonconformists (unlike the Tory party at the time), so I can speculate that the Whig party may have been more sympathetic towards the Chartists than the Tory party would have been, if they were in government instead, but possibly even they may not have allowed the three petitions the Chartists gave to Parliament based on the ideal of “The People’s Charter”. Chartism was despised by many MPs and the elite ruling class for wanting to grow the franchise of voters(6). Basically, the upper classes wanted to keep the voting power to themselves and let the electoral districts and Boroughs be run by rich families instead of anybody who is a male over the age of 21 who “is of right mind”.

The Lancaster Connection

I am interested in the Chartist movement because some of their activities occurred around my local area of Lancaster. For example, around March 1843,

“A total of 59 men went ontrial at Lancaster assizes the following March, charged in what the Chartists dubbed the ‘monster indictment’ with nine counts of inciting riots, risings, strikes and other forms of disorder. Among them was Feargus O’Connor, publisher of the Northern Star and leading light of the National Charter Association.”

The trial in Lancaster Castle lasted eight days and the attorney general ran the proceedings himself (7). During the trial, two former Chartists gave evidence that was damning for the 59 men being accused but, surprisingly, charges were dropped against seven men, nineteen others were acquitted and the rest only had one or two charges against them out of a possible nine, but the sentencing was adjourned and never passed. This was a huge blow for the Chartist movement as it’s leader for some years now, Feargus O’Connor, had been in custody and the movement lost momentum after that, declining in popularity until it’s effective abolition in 1851.

... a Grand National Holiday (General Strike) would result in an uprising and a change in the political system.

A Major Contributor to the Movement

George Julian Harney was was born in Deptford (South London) on February 17th 1817 (8). He attended a Naval School but afterwards, instead of pursuing a career in the navy, he became an apprentice in a shop to Henry Hetherington, editor of the ‘Poor Man’s Guardian’ – for which he was imprisoned three times, and friends with William Lovett who helped start the Chartist movement. This apprenticeship left a radical ideal in Harney’s mind and he decided to join the London Working Men’s Association, which Lovett had set up. However, he became increasingly frustrated as he thought the Association wasn’t having any impact and Harney began to prefer the more militant ideas of Feargus O’Connor. Soon after January 1837, Harney became convinced of William Benbow’s theory that “a Grand National Holiday (General Strike) would result in an uprising and a change in the political system” (9). At a Chartist meeting in summer 1839, Harney and Benbow tried to convince Chartists to go on a general strike and even toured the country to persuade workers to join, but instead they were both charged and arrested for making seditious speeches, so the general strike was called off. He had failed with the idea of a strike and decided to exile himself to Scotland. However, the following year he became a Chartist organiser in Sheffield. George Harney was one of the 59 Chartists arrested in the strikes of 1842 and he was tried at Lancaster in March 1843. After he appealed his sentence at Lancaster, he began working for Feargus O’Connor on his newspaper the Northern Star and two years later became editor. After that he spent the rest of his life writing for various newspapers, including his own, The Red Republican (later shut down due to financial losses), until his death on the 9th December, 1897.

The Legacy

The legacy of Chartism was prominent in the minds of MPs even after the decline of the movement. The People’s Charter was not enacted. So, in the short term, Chartism failed, but it was a movement founded on optimism that was eventually met with success (10), as shown by the fact that by 1918, five out of six Chartists’ demands had been met, the exception being Parliamentary elections occurring annually. This is because by the 1850s, MPs accepted that further reform was needed, ergo, further Reform Acts were passed in 1867 and 1884 (11). The political imagination and the dissident acts of the early Chartist campaigners are the authentic roots of many of today’s political freedoms.

- 1 http://www.bl.uk/learning/histcitizen/21cc/struggle/chartists1/historicalsources/source2/reformact.html

- 2 http://www.bl.uk/learning/histcitizen/21cc/struggle/chartists1/introduction/historyofchartism.html

- 3 http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/politics/g7/

- 4 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1838_in_the_United_Kingdom

- 5 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_Whig_Party

- 6 http://www.bl.uk/learning/histcitizen/21cc/struggle/chartists1/summary/chartism.html

- 7 http://www.chartists.net/LancasterTrial1843.

- 8 http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/CHharney.htm?menu=chartism

- 9 http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/CHgeneral.htm

- 10 http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/victorians/chartist_01.shtml

- 11 http://www.parliament.uk/about/livingheritage/

- transformingsociety/electionsvoting/chartists/overview/chartistmovement/