In many ways, the experiences of conscientious objectors have remained ‘silent histories’ in the annals of war. By analysing the content of his school’s wartime magazines, Lancaster Royal Grammar School student, Tom Breheny, begins to look at how and why this is the case and starts to give a voice to those silent individuals.

Silent Histories from Lancaster Royal Grammar School: Changing attitudes to conscientious objection at the school and the service of former pupils in the Friends Ambulance Unit

Posted by Tom Breheny, Lancaster Royal Grammar School

As a student at Lancaster Royal Grammar School, I am faced everyday with reminders of my school’s historic and current link with military life. The Memorial Library, the Memorial sports pitches and the Combined Cadet Force are all monuments to the school’s connections with warfare. Therefore, it should come as no surprise that the school’s attitude to war, especially during the First World War, was very positive and any dissent from this notion would have been nigh impossible to voice.

Attitudes to War at the School During World War 1

The Lancastrian, the school magazine, provides a snapshot of this attitude with this quotation from 1915:

‘Now is the time for every British schoolboy to do his utmost to train himself to help fight his country’s battles in the future, if needs be, and the very best course open to him to follow while at school is to join the O.T.C. [Officer Training Corps, the predecessor to the Combined Cadet Force], and then not to shirk parades or the tediousness of the preliminary drills, but to go “all out” to make himself worthy of the title British’. (December 1915: 284)

From this fiery rhetoric, we can tell that the school had been swept up in the patriotic fervour of the First World War, going as far as implicitly stating that supporting the war effort was intrinsically linked with being British. The debating club, known as the Whewell Society, also gives a valuable insight into the lack of opposing voices to this war in that there were very few motions concerning the war (let alone the morality of it). One motion in particular that ‘There will be no Armies after this war’, proposed in 1915, was defeated by 13 votes to two (The Lancastrian, March 1915: 209-10).

The Memorial Library, the Memorial sports pitches and the Combined Cadet Force are all monuments to the school’s connections with warfare.

Because of these attitudes at the school, any information on conscientious objection in the First World War is incredibly difficult to find. There were a few students the school recognises who served in exclusively non-combatant services, such as ambulance drivers with the French Red Cross. However, the matter of conscientious objection was still taboo in the school and the term is never mentioned in the school magazine.

Acknowledging Conscientious Objection at the School During World War 2

In stark contrast, by the outbreak of the Second World War, the ethics of war and of conscientious objection were being actively debated within the school. A motion was debated in the Whewell Society in 1941 (at the height of the Blitz) that ‘In the opinion of this House men should not be excluded from Military Service because of conscientious objection’ (The Lancastrian, 1941: 92). It was defeated by one vote.

Another sign of the changing attitudes to war is that it looks like two conscientious objectors were listed in the school’s Roll of Honour, published in The Lancastrian throughout World War 2. William E. Moore and Albert H. Tomlinson were both former pupils who joined the Friends Ambulance Unit (FAU).

Friends Ambulance Unit

The Friends Ambulance Unit had its origins in the First World War when it was originally called the Anglo-Belgian Ambulance Unit. It was formed by Quakers (who made up the majority of its members) who, because of their religion and beliefs, could not and would not take arms or kill but still wanted to serve their country. That said, the FAU wasn’t exclusively a Quaker outfit and was open to anyone willing to serve, regardless of their beliefs. It sent over a thousand men to serve as ambulance drivers on the Western Front and, doubtless, saved countless lives. Even on the first passage over to France they came across a Royal Navy ship in distress and managed to rescue many of the crewmembers (Tatham and Miles, 1919).

Now is the time for every British schoolboy to do his utmost to train himself to help fight his country’s battles in the future, if needs be, and the very best course open to him to follow while at school is to join the O.T.C. (Officer Training Corps, the predecessor to the Combined Cadet Force), and then not to shirk parades or the tediousness of the preliminary drills, but to go 'all out' to make himself worthy of the title British.

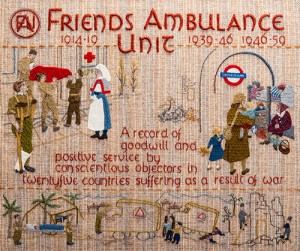

Quaker Tapestry Panel – Friends Ambulance Unit – Quaker Tapestry © Image is one of the 77 illustrations known as the Quaker Tapestry which is a community textile of embroidered panels made by 4,000 people from 15 countries. The exhibition of life, revolutions and remarkable people can be seen at the Quaker Tapestry Museum in the Quaker Meeting House in Kendal, Cumbria UK. www.quaker-tapestry.co.uk

The FAU was disbanded in 1919. However, during a reunion of former members in 1938 after the Munich crisis and with the spectre of war looming over Europe once again, plans were made for the formation of another FAU unit which was formally created in September 1939. Members went on to serve as ambulance drivers and medical staff both at home during the Blitz and overseas in places such as Scandinavia, Greece, China, France (even during D-Day) and Germany. The FAU was disbanded in 1946 but was replaced by the Friends Ambulance Unit Post-War Service which survived until 1959. The work of the FAU was noted as a key reason as to the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to Quakers worldwide in 1947 (Davies, 1947).

Shifts in Attitude Towards War and Pacifism During the Two World Wars

On the whole, it seems like the attitudes of Lancaster Royal Grammar School were simply products of their time. In WWI it took on the nationalistic, aggressive, dutiful tone that was prevalent at the time but towards the start of the Second World War, and indeed during it, it was much more accepting of dissenting views towards war. To make such a leap in mentality was mainly the result of a greater societal leniency and aversion to war after the horrors and unprecedented loss of life in the First World War, as the popularity of the works of objectors such as the author and poet Siegfried Sassoon and philosopher Bertrand Russell show. The school’s acceptance of conscientious objection is a testament to our society’s increasing moral conscience and our increasing rejection of conflict.

A motion was debated in the Whewell Society in 1941 (at the height of the Blitz) that ‘In the opinion of this House men should not be excluded from Military Service because of conscientious objection.

- Davies, A. 1947. Friends Ambulance Unit. London: published for the Council of the Friends Ambulance Unit by G. Allen and Unwin.

- Tatham, M. and Miles, J. 1919. The Friends Ambulance Unit. London: The Swarthmore Press Ltd.

- The Lancastrian, Magazine of the Royal Grammar School, March 1915. Lancaster.

- The Lancastrian, Magazine of the Royal Grammar School, December 1915. Lancaster.

- The Lancastrian, Magazine of the Royal Grammar School, July1941. Lancaster.

- Quaker Tapestry Panel – Friends Ambulance Unit – Quaker Tapestry © image is one of the 77 illustrations known as the Quaker Tapestry which is a community textile of embroidered panels made by 4,000 people from 15 countries. The exhibition of life, revolutions and remarkable people can be seen at the Quaker Tapestry Museum in the Quaker Meeting House in Kendal, Cumbria UK Further information: www.quaker-tapestry.co.uk