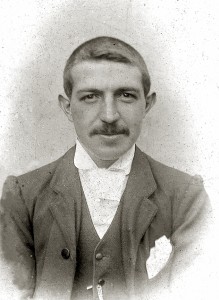

Henry Alty, a joiner from Pilling, objected to the war on religious grounds. He was court martialed at Oswestry, where he was subject to brutality. Following concerns about his treatment, questions were raised in the House of Commons. After Oswestry, he was sentenced to 91 days’ hard labour at Wormwood Scrubs. Henry was my great grandfather, though I don’t really remember him as I was only three years old when he died in 1959, at the age of 79.

Henry Alty: A Man of Principle

Posted by Angela Norris

Family Background

Henry was born in Pilling, in the Garstang Rural District, on November 8, 1879. The 1911 Census records that he lived at Vine Cottage, Pilling, with his father Thomas James (Jas) Alty, by then a widower, and sisters, Alice and Mary Ellen. At the time of the census, Henry was 30 and single. He worked for Pilling firm, Stafford Brothers, who were joiners and undertakers.

Wartime Objection

Henry was 35 by the time he was conscripted in 1916. He objected to war on religious grounds, citing his religion as ‘Primitive Methodist.’

The Pearce National Database of Conscientious Objectors states that he was given one month’s exemption from war at the request of his employers, Stafford Brothers, at the Military Service Tribunal in Garstang [1].

Military records show he was called to join the 4th R battalion of the King’s Own Royal Lancaster Regiment, on September 4, 1916 [2]. His first military service number was 5429. However, this was changed in 1917, following renumbering of the Territorial Force. According to regimental records, Henry was transferred to Class W (T) on November 9, 1916. Class W was a category of Army Reserve and the ‘T’ would have denoted that he was a Territorial, and no longer part of the 4th Battalion. The reasons for this change of category to Army Reservist are likely to have been linked to what happened later, when Government policy towards C.O.s changed (see below). After he ignored his call-up papers, he was arrested as an absentee on September 26, 1916 and court martialed.

Mr Chancellor asked the minister if he was aware of Henry Alty being subjected to “persistent ill treatment by being tied from shoulder to shoulder with a rope and then on to a barrow handle; whether he was aware that he was then dragged along by men on either side while another forced his head back and he was prodded from behind with a sharp instrument until he collapsed on the floor, and that he was then dragged some considerable distance and afterwards thrown on top of the barrow.”

Brutality: Questions Asked in the House of Commons

Henry was court martialed at Park Hall Camp, Oswestry, on October 6, 1916. The Pearce database describes how he was subject to levels of brutality that were serious enough for questions to be raised in the House of Commons, on December 4, 1916.

The Hansard Parliamentary records show the level of cruelty to which he was exposed [3]. During a debate between Mr Chancellor, a Liberal MP from London, who took an interest in the welfare of C.O.s, and the Secretary of State for War, Hugh Arnold Forster, Mr Chancellor asked the minister if he was aware of Henry Alty being subjected to “persistent ill treatment by being tied from shoulder to shoulder with a rope and then on to a barrow handle; whether he was aware that he was then dragged along by men on either side while another forced his head back and he was prodded from behind with a sharp instrument until he collapsed on the floor, and that he was then dragged some considerable distance and afterwards thrown on top of the barrow.”

Mr Chancellor asked what action Mr Forster planned to take in relation to Henry Alty’s treatment and in relation to another C.O., a Private Robinson, who had been subjected to similar abuse.

In response, the minister claimed: “The facts are not as stated.” He went on to say that the incidents which led to the allegations of ill-treatment took place some time during August and that both men, “although refusing to obey orders” had been remanded for court martial hearings in September, but had not in fact been remanded for trial by court martial.

Mr Forster added that both men had been seen daily by their commanding officer and when asked whether they had any complaints to make or anything to say, they both invariably answered, “No, thank you.”

The minister’s response to the allegations of brutality raises some interesting, and concerning questions: was Henry’s response in answer to the questions raised by his commanding officer a show of stoicism and bravery in the face of unimaginable cruelty? Or was it, as might have been more likely, the response of someone under duress, and fearful of the consequences to himself and his fellow C.O.s if he spoke against the harsh realities of military regime? In other words, was there a ministerial cover up of vital evidence?

Whatever lay behind Mr Forster’s reply to Mr Chancellor’s question, it is significant that the Society of Friends took an interest in Henry’s case because of the brutality allegations. A handwritten record of his case history can be found in the files produced by the Visitation of Prisoners Committee [4], located at the Friends (Quaker) Library in London, though the information is sketchy and does not go into any details about his treatment. Barrett (2014) refers to the brutality allegations meted out to Henry and other C.O.s in his book, Subversive Peacemakers: War-Resistance, 1914-1918: An Anglican Perspective [5].

Although he never discussed his experiences, he developed an aversion to uniforms and could not bear to see anyone wearing one. My dad remembers how, as a child, he was cautioned against wearing his cub scout uniform in Henry’s presence.

Hard Labour in Wormwood Scrubs

After court martial, Henry was sentenced to 91 days’ hard labour at Wormwood Scrubs. Conditions in prison were harsh, with C.O.s not only forced to endure a strict punitive regime but also experiencing starvation and hardship caused by reduced rations. In his book, Conscription to Conscience: A History, 1916-1919, Graham (1922) points to the way C.O.s, ostracised and ridiculed as shirkers by wider society, were deemed unworthy of food when there was a national food shortage, with vital food products needed to support the frontline troops [6]. This led to questions being raised in the House of Commons by Mr Chancellor about the levels of starvation experienced by C.O.s in Wormwood Scrubs. In response Mr George Cave said, “There is no foundation for the statement that rations have been reduced by half” [7].

Over time, conditions did improve as part of a wider move to replace incarceration with a more humane regime in recognition of the role C.O.s could play in supporting the war effort with alternative work, following the establishment of the Brace Committee. Graham describes how prisoners were brought “weakened and exhausted from their cells, in total ignorance of what was before them, to a Tribunal within prison walls…the majority of the men were passed as genuine after being sent back to prison to await their verdict” (Graham, 1922).

Following the Central Tribunal, an offer was made to transfer prisoners to Section W of the Army Reserve, in which they would cease to be subject to military discipline and the Army Act. This may help to explain why Henry’s military records show he was transferred from his regiment to Section Class W (T), denoting his change to army reservist.

Information from the Pearce data base shows that Henry Alty went before a Central Tribunal at Wormwood Scrubs and was classed as a Category ‘A’ ‘genuine’ Conscientious Objector and he agreed to alternative work under the Brace Committee system.

Joining Home Office Work Scheme

From Wormwood Scrubs, Henry was sent to Wakefield Work Centre, in Yorkshire, which was established as part of the Home Office Work Scheme. Here, according to a report in the Manchester Guardian, cited in Graham (1922) [8], changes had been made to the former prison environment: locks had been removed; warders were no longer in uniform and they acted as instructors rather than prison officers; and C.O.s were involved in work such as mailbags. Inmates were given concessions relating to correspondence and visitors, and they were each allowed three pence a day to spend in the canteen.

Bibby’s Oil Cakes

From Wakefield, Henry was transferred to J. Bibby and Sons Oils factory in Liverpool. The factory was involved in producing edible oils, which were seen as vital for increasing food production during the war. Questions about the role of Bibby’s were raised during the House of Commons by Mr Thomas Richardson. Hansard parliamentary records report that Mr Richardson asked how many C.O.s had been transferred from Wakefield to the Liverpool factory and what their rates of pay were [9].

In reply, Mr Brace, the Under Secretary of State for War, said that 25 C.O.s were employed under the control of the Committee on Employment of Conscientious Objectors at the Liverpool Centre. He stated that Messrs Bibby had applied to the Committee for labour on the grounds that the work the men were doing was of national importance, and they were very short of men. In addition to housing, feeding and clothing, the men were being paid 8d per day, with extra allowances for wives and children where appropriate.

Henry’s case notes from the Library of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) state that after Bibby’s Cake Oils, Henry was moved to another Home Office work placement in Morpeth, Northumbria. This was at Witton White Houses, operated by Ewesley and Company, near Morpeth.

After the War

After the war Henry returned to his home in Pilling. He married Elizabeth Ann France, from Quernmore. The couple had two sons, Robert, who was my grandfather, and Ronald, who died during childhood from peritonitis, and a daughter, Freda. Henry resumed his role with Stafford Brothers. He also opened a fish and chip shop in a wooden building next to his home. He bred bantams and attended shows all over the country. My dad remembers him as a rather eccentric character who used to travel to shows by rail, carrying his bantams in a cage.

It is evident that Henry bore the scars of his treatment as a C.O. long after the war finished. Although he never discussed his experiences, he developed an aversion to uniforms and could not bear to see anyone wearing one. My dad remembers how, as a child, he was cautioned against wearing his cub scout uniform in Henry’s presence.

Henry reared bantams but could not bring himself to kill them and would send them to the farm across the road to be slaughtered there. He became disillusioned with the church and his religious beliefs waned. He died on May 7, 1959.

Henry was a man who stood up for his principles. I’m only sorry I never knew him.

Henry was a man who stood up for his principles. I’m only sorry I never knew him.

- Pearce National Database of C.O.s.

- Military Service records – obtained from Mr Peter Donnelly, King’s Own Royal Lancaster Regiment, Regimental Museum, Lancaster Museum.

- Hansard Papers: 4 December 1916, vol 88, cc 668-9w.

- Case notes, Library of the Religious Society of Friends in Britain: K:\Collections\Archives\Central Organisation\Visitation of Prisoners Committee VOPC Cases 02.xls

- Graham, J.W., 1922. Conscription and Conscience: A History, 1916-1919. London: Allen & Unwin.

- Barrett, C., 2014. Subversive Peacemakers: War-Resistance, 1914-1918: An Anglican Perspective. Cambridge: The Lutterworth Press.

- Hansard Papers: 31 July 1917, cited in Graham J.W. op cit.

- Manchester Guardian report on conditions in Wakefield Home Office Scheme, 17 September 1917, cited in Graham J.W. op cit.

- Hansard Papers: 3 April 1917, vol 92, cc 1096-7.