The experience of Walter Ashworth, brother of Albert Ashworth, as a conscientious objector in World War One is far from typical. As a man with artistic training he was able to seek out work of national importance that led him to work on the earliest moving prosthetic limbs, an area of technical advancement that emerged in response to the increasing numbers of amputees returning from the conflict.

The Ashworth Brothers: Walter Ashworth – Seeking Work of National Importance in World War One

Posted by Ann Morgan

Prior to World War One

Walter decided not to join the long-established family boot and shoe making and selling business in Drake Street, Rochdale. The 1911 census records him as an art student boarding in Fulham, London. He was probably a student at The Royal College of Art. [1] Biographical information in the Herbert Art Gallery and Museum City of Coventry shows him as a member of the Royal College of Art. [2] In 1911 Walter graduated, became an art master in Ipswich and married Alice Healey, also from a Drake Street shop-keeping family in Rochdale. They had a daughter, Joan, in 1914.

Decision and disagreement within the family

Family letters reveal that Walter discussed becoming a conscientious objector from early in 1916 when the Military Service Act brought conscription into law. [3] They also indicate that Alice’s family was opposed to this. In a letter to Alice his sister-in-law, Mary Healey, questions Walter’s motives. She writes:

‘…don’t you think there is a strong suggestion of selfishness in the attitude of a conscientious objector. I do not except Walter from this, for I once heard him say ‘I shall get all I can out of this world, never mind anybody else,’ this by the way in upholding socialism… It was not what he said, so much as how he said it, that makes me think he is not wholly genuine in his conscientious objection…’

Alice’s father was equally blunt in a letter to Alice dated 10 May 1916:

‘You know my unalterable opinion on the war and what I think is everyone’s duty… But if you do come I wish you to understand that I will have none of your dammed fads discussed in my presence.’

Mary withdrew her comments later. Walter appears to have convinced her of his sincerity in what she calls his ‘treatise’. She says:

‘I withdraw all I said and henceforth and for ever more will be more discriminating in my remarks about C.O.s. …I am in no way converted to your way of thinking, though I think you have one or two good points on your side.’

She responded to these one by one, still chastising him by telling him he had a cheek to quote Christian doctrines and beliefs ‘when you have openly denied Christian doctrines during the last six years.’

Walter appealed for support at his tribunal from his friend, Joe B. in Loughborough. In a letter, Joe agreed to write to the tribunal stating that Walter had spoken against war in every shape and form and that he knew him to be a ‘deep objector to war.’

‘You know my unalterable opinion on the war and what I think is everyone’s duty... But if you do come I wish you to understand that I will have none of your dammed fads discussed in my presence.’

The appeal tribunal

A newspaper transcription of Walter’s second military tribunal states that he:

‘had been exempted from military service as long as he remained at work on the farm on which he was engaged when he made his application for exemption… he had taken up this work voluntarily as he wished…during his vacation to do work of real national importance during that time. The appellant said that the farmer could not guarantee to employ him after 29 September. As he could not stay on the farm the condition of his exemption would be broken.’ [4]

Walter asked to be transferred to the Pelham Committee so that he would be able to do other work of national importance making artificial limbs and was given 21 days to find that work.

A second letter from Joe B., dated 21 May 1916 and written well before this tribunal, indicates that Walter had had this idea in mind for a long time. Joe writes ‘I think your proposal to take on the making of artificial limbs is a notion of the highest order of inspiration.’

‘I withdraw all I said and henceforth and for ever more will be more discriminating in my remarks about C.O.s. ...I am in no way converted to your way of thinking, though I think you have one or two good points on your side.’

Further work of national importance

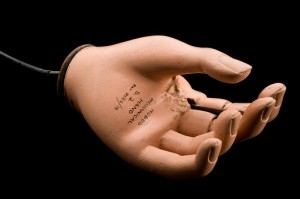

Hobbs-type artificial left hand, Europe, 1918 Image and text courtesy of Science Museum / Science & Society Picture Library – http://scienceandsociety.co.uk/results.asp?image=10626232

Walter found that work in Balham, London. In a letter to Walter from Flying Officer, Bernard A. B. Shore (77 Squadron Royal Flying Corps), dated 28 November 1917 we learn that the limbs he worked on were arms with moving fingers. Bernard writes ‘The fingers are working marvellously well… I just spent a few minutes at my old hospital the other day. The Matron and Sisters there were simply astonished at them.’

Did Walter work with Edward Walter Hobbs, one of the foremost makers of moving artificial limbs in World War 1? In 1917 Edward lived at 76 Station Road, Balham, working as a consulting engineer. [5] Walter at that time was living at 1 Heslop Street, Balham. [6] Edward’s father was Joseph Walter Hobbs [7], and one of the family letters to Walter, dated 22 December 1919, is from J. Walter Hobbs. Bernard Shore concludes his letter to Walter ‘I shall not feel serene until I have things finished and been able to thank you and Mr Hobbs more substantially than with pen and ink.’ This letter establishes a clear link between Walter, Hobbs and Bernard’s artificial limb.

The photograph of the Hobbs-type artificial left hand held at the Science Museum is similar to that described by Bernard Shore:

Painted flesh coloured for a realistic appearance, the index and middle finger of this prosthetic left hand are jointed and can move towards the thumb, which along with the other two fingers is immobile. The hand was made by a man named Hobbs, a contractor employed at Queen Mary’s Hospital in Roehampton, England. This institution was established in 1915 to deal with the growing number of amputees returning from fighting the First World War. Hobbs applied for a patent for this design in 1918. Improvements and innovations in the design and materials of artificial limbs occurred during the First World War, during which over 41,000 British servicemen lost one or more limbs.

‘The fingers are working marvellously well… I just spent a few minutes at my old hospital the other day. The Matron and Sisters there were simply astonished at them.’

Life after World War One

By 1919 Walter had returned to teaching and in 1926 he became Principal of the Art College in Coventry. He was a Rotarian and Chairman of the Warwickshire Society of Artists, giving many addresses to the Society and exhibiting watercolours in their exhibitions. He exhibited several works in the Royal Academy and was a war artist in Coventry during World War 2. Pictures held by Coventry Art Gallery and Museum include street scenes and the hospital and Cathedral after bombing raids. They are used in exhibitions about Coventry in World War 2. Walter died in Coventry in 1952, aged 69. Alice died in Kent in 1958, aged 71.

- [1] 1911 Census.

- [2] Herbert Art Gallery and Museum/City of Coventry Libraries, Arts and Museums Department, 1980. A Survey of Public Art in Coventry. Coventry.

- [3] All references in this article to Walter’s personal correspondence are from transcriptions of letters held by the Ashworth family who have kindly permitted us to quote from them here.

- [4] Transcript from an unnamed newspaper of the East Suffolk appeal tribunal amongst the Ashworth family papers.

- [5] 1917 Post Office County London Directory.

- [6] Transcription of a letter to Walter from Committee on Work of National Importance, Strand, London WC2, dated December 1917.

- [7] 1911 Census.

- Special thanks go to the Ashworth family for sharing their family archives and helping with the research for this article.