From the beginning of their organisation, Quaker Friends believed that all persons are equal in God’s eyes and Quakers were active in denouncing slavery and campaigning for its abolition. However, living in a port town that prospered directly from the Triangle Trade, Lancaster Friends found themselves in a difficult position regarding the Quaker stance on slavery, as Marcie Holmes describes in this article.

Lancaster Quakers and the Transatlantic Slave Trade

Posted by Marcie Holmes

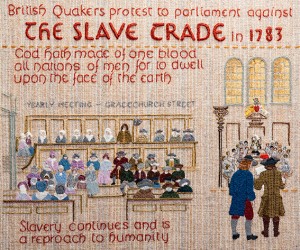

QUAKER TAPESTRY PANEL – THE SLAVE TRADE: Quaker Tapestry © This image is one of the 77 illustrations known as the Quaker Tapestry which is a community textile of embroidered panels made by 4,000 people from 15 countries. The exhibition of life, revolutions and remarkable people can be seen at the Quaker Tapestry Museum in the Quaker Meeting House in Kendal, Cumbria UK http://www.quaker-tapestry.co.uk

There is very little surviving evidence about how early Lancaster Quakers viewed slavery and the transatlantic slave trade, even though these were the most compelling human rights issues of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. While Quakers in London took a public stand against the making and owning of slaves, Lancaster Quakers apparently did not record their dissent for others to see. The issue may have been a source of disagreement among Lancaster Quakers as some were involved in businesses that profited from the enslavement of Africans.

Quaker Stance on Slavery

Since the beginning of their organisation, Quaker Friends have believed that all persons are equal in God’s eyes. This led many early Quakers to denounce slavery and to fight for its abolition at a time when many Britons refused to see dark-skinned people as anything like light-skinned ones. In 1676, the founder of Quakerism, George Fox, reminded Friends of the human dignity of African slaves after he visited Barbados and saw the plight of the slave labourers there. He wrote:

‘…if you were in the same condition as the Blacks are…now I say, if this should be the condition of you and yours, you would think it hard measure, yea, and very great Bondage and Cruelty. And therefore consider seriously of this, and do you for and to them, as you would willingly have them or any other to do unto you…were you in the like slavish condition’ [1].

‘...if you were in the same condition as the Blacks are…now I say, if this should be the condition of you and yours, you would think it hard measure, yea, and very great Bondage and Cruelty. And therefore consider seriously of this, and do you for and to them, as you would willingly have them or any other to do unto you…were you in the like slavish condition’ - 1.

As early as 1727, Quakers used their London Yearly Meeting to publicly denounce the slave trade. In 1761 the Yearly Meeting recommended that any Quakers found to have slaves should be disowned from their religious community. Having tried to put their own house in order, the Yearly Meeting of Quakers then called for slavery to be abolished throughout the world, starting with a petition to Parliament in 1783.

Lancaster Quakers Involved in the Slave Trade

Yet despite many Quakers’ public opposition to slavery, some Friends struggled to find their own stance on the issue. Some Quakers even personally profited from the Triangle Trade that led to the enslavement of hundreds of thousands of Africans. A few of these controversial Quakers lived in Lancaster, which during the Georgian era rivalled Liverpool in the scale of its participation in the Triangle Trade.

Local historians have recently called attention to how Lancastrians, including some Quakers, created wealth for themselves and their town through businesses that relied on the capture and trading of slaves. One such Quaker was Thomas Rawlinson (1751-1802), whose West Indies business interests included a plantation with several slaves as well as ships that transported slaves between colonies. Rawlinson was not disowned by his fellow Quakers for this, but instead for another infraction of Quaker practice: equipping his ships with guns to protect their cargo.

Local historians have recently called attention to how Lancastrians, including some Quakers, created wealth for themselves and their town through businesses that relied on the capture and trading of slaves.

Another Lancaster Quaker who participated in the enslavement of Africans was Dodshon Foster (1730-1793). As a young man in the 1750s, Foster owned a 40-ton ship, Barlborough, which carried enslaved people from Africa to the Caribbean, and then carried goods like sugar, rum and mahogany back to Lancaster to be sold for profit. He also owned shares in two other Triangle Trade ships.

Foster eventually disentangled himself from the slave trade, investing his money in other business ventures. This may be because many Lancastrian Quakers believed the slave trade business lacked respectability, and Foster wanted to be respectable. As the historian Melinda Elder has noted, the wealthiest and most influential Quakers in Lancaster avoided participating in businesses linked to the slave trade, though this may have been due to the financially risky and speculative nature of the slave trade in Lancaster rather than its moral horrors [2].

The Response of the Lancaster Meeting House

The surviving historical records say almost nothing about what the Lancaster Quakers thought about Rawlinson and Foster’s business dealings. We are left to wonder: were they sympathetic to these men’s desire to create wealth, a desire that brought new vibrancy to the town of Lancaster? Or were they concerned that businesses that relied on slavery were an affront to Quaker belief, and an affront to human dignity? Did they ignore the issue, thinking it was not important or that it would go away? The records of the Lancaster Quaker Meeting do not reveal any debates over Rawlinson’s or Foster’s dealings, perhaps because the Meeting’s clerks mainly recorded the matters in which the Meeting’s members were in general agreement. It may be that Lancaster Quakers’ involvement in the slave trade was too contentious to be included in official documents. Their private discussions have been lost to history.

We are left to wonder: were they sympathetic to these men's desire to create wealth, a desire that brought new vibrancy to the town of Lancaster? Or were they concerned that businesses that relied on slavery were an affront to Quaker belief, and an affront to human dignity?

- [1] George Fox, Gospel-Family Order, Being a Short Discourse Concerning the Ordering of Families, both of Whites, Blacks and Indians (1676).

- [2] Melinda Elder, The Slave Trade and the economic development of 18th century Lancaster (Krumlin, Halifax: Ryburn Publishing 1992), pp.116-117.