While Lancaster was not at the forefront of the movement to abolish slavery in the early nineteenth century in Britain, there was evidence of some abolitionist activity in the town, some of which was led by Quakers. This activity included the promotion of the Free Produce Movement the spirit of which, as Marcie Holmes explains in this article, can be seen to live on today in our region’s spearheading of the campaign for Fair Trade.

Lancaster Quakers and the Campaign to Abolish Slavery

Posted by Marcie Holmes

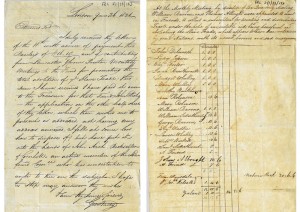

Letter from Quaker abolitionist, George Stacey, to the Lancaster Quaker Meeting, 1821: Document held in the records of the Lancaster Quaker Meeting at the Lancashire Archives, Preston

Lancaster was not home to any large, nationally-known anti-slavery societies. In the early nineteenth century, as national campaigns to abolish slavery gathered steam in the United States and Britain, Lancaster had long ceased to be a port in the Triangle Trade and had lost much of the wealth that it had gained from its earlier involvement. As nearby cities swelled in size, it remained a small town. Yet though Lancaster’s residents were not at the radical forefront of the Anti-Slavery Movement, we can be sure that they knew about the abolitionists’ campaigns, and that they talked among themselves about the issues that these campaigns raised. There is evidence of some abolitionist activity in Lancaster, some of which was led by Quakers. While Lancaster’s Quaker abolitionists may not have often expressed their dissenting opinions on the national stage, they still found ways to make their opinions known and to influence their community for the better.

The Move Towards Abolition in the 1830s

Parliament outlawed slavery in the British Empire in 1833. Several months before, in July 1832, the secretary for the Lancaster Anti-Slavery Society, Thomas Hodgson, wrote to two local peers and two Members of Parliament who represented areas around Lancaster. Hodgson asked them to put in writing their stance on the abolition of slavery. Their cautious responses, which were published in the Lancaster Gazette [1], suggest what Lancaster’s abolitionists were up against. All four men responded that, while they opposed slavery in principle, they worried that a rush to emancipate slaves would ruin the economies of the British Atlantic colonies, and also hurt the slaves because their years of enslavement made them not yet ‘fit’ for freedom.

Yet though Lancaster's residents were not at the radical forefront of the Anti-Slavery Movement, we can be sure that they knew about the abolitionists' campaigns, and that they talked among themselves about the issues that these campaigns raised.

Even the M.P. for Lancaster, Thomas Greene, who had previously submitted petitions to Parliament against slavery, explained that he believed that the slaves should not be immediately emancipated, but that Britons should ‘do the utmost in our power to prepare and fit them for a state of liberty.’ Presumably, in Greene’s thinking, Parliament would later determine when the slaves were spiritually and intellectually ready for their freedom. Greene’s answer to Hodgson’s question suggests how the established political interests in Lancaster wanted to maintain the status quo for as long as possible. The M.P.s’ and Lords’ responses also exemplify how by the 1830s most Britons agreed that slavery was morally wrong even as they disagreed about what to do about it. British opinion had turned against slavery through the efforts of abolitionists who spread information about the shocking realities of slavery in British and American territories. Local abolitionist groups were very important to the success of this national campaign to change public opinion, as these groups did the groundwork of raising funds, handing out pamphlets, hosting speakers, and – as we just saw in the exchange in the Lancaster Gazette – keeping the problem of slavery a topic of local debate.

Lancaster Quakers and the Abolition Movement

Lancaster’s Quakers played a part in these grassroots efforts. An 1821 letter from the great Quaker abolitionist George Stacey, found in the records of the Lancaster Quaker Meeting, reveals that Quakers in Lancaster and Preston collected 16 pounds and 15 shillings for the Fund for Promoting the Total Abolition of the Slave Trade, an amount that was the equivalent of more than 100 days of wages for a typical craftsman at that time [2]. The Lancaster and Preston Quakers had made the donation ‘under the hope of our suitable aid being beneficial in abolishing the Slave Trade, which appears to have been continued by some Nations with its usual horrors and sad consequences’. Later, in April 1845, Lancaster Friends decided to form their own Anti-Slavery Society in order to circulate anti-slavery texts, and to express their unified solidarity with American Friends who had been imprisoned while fighting for the freedom of slaves [3].

Even the M.P. for Lancaster, Thomas Greene, who had previously submitted petitions to Parliament against slavery, explained that he believed that the slaves should not be immediately emancipated, but that Britons should 'do the utmost in our power to prepare and fit them for a state of liberty'.

Lancaster Quakers’ involvement in the abolition movement may have gone beyond supporting political campaigns to abolish slavery. Quakers throughout Britain were concerned about the morally corrosive effects of buying and using the products of slaves’ labour. They saw the consumption of slave-grown sugar or cotton as bolstering the system of slavery, and the money saved by buying these cheap goods as profit from the oppression of their fellow human beings. As one Quaker author explained:

‘Does not every pound of Slave-grown sugar, purchased for a British home, form a part of the bribe to the kidnapper of a human being from his home in Africa? And is not every rejected article of the Slave’s labour a contribution on our part to the purchase of his freedom?’ [4]

Free Produce Movement

Motivated by sentiments like these, British and American Quakers were instrumental in promoting the ‘Free Produce Movement’, which sought to convince consumers to choose sugar, coffee, rice and cotton that was grown in non-slave holding territories, or to go without these items entirely. The Free Produce Movement of the early nineteenth century grew out of the British sugar boycott of the 1790s, which had successfully brought attention to the fact that most sugar in Britain was harvested by slaves. The movement continued until the 1860s, when the United States finally abolished slavery.

An 1821 letter from the great Quaker abolitionist George Stacey, found in the records of the Lancaster Quaker Meeting, reveals that Quakers in Lancaster and Preston collected 16 pounds and 15 shillings for the Fund for Promoting the Total Abolition of the Slave Trade, an amount that was the equivalent of more than 100 days of wages for a typical craftsman at that time.

An important aspect of the Free Produce Movement was spreading the word about where consumers could purchase free-labour alternatives. After Parliament abolished slavery in British territories, consumers had easier access to free-labour sugar, coffee and rice, but it was particularly difficult to find free-labour cotton as almost all of the cotton that Britain imported was produced in the United States. Only a few sellers were known to stock free-labour cotton, a short list that included Quaker wholesalers in Manchester, Liverpool, London, and also the Lancaster firm Barrow and Satterthwaite, which was a source for grey and white calicoes, as well as cotton for knitting [5].

Fair Trade Movement

In some ways, local Quakers’ involvement in the Free Produce Movement lives on in the modern Fair Trade movement, which seeks to give farmers in developing countries a fair price for their produce. By calling attention to the treatment of farmers, organisations like the Fairtrade Foundation encourage consumers to consider the social and economic effects of their purchases. Quakers have long embraced this movement by promoting products like Fairtrade-certified sugar, coffee, and chocolate. In 1994 a Quaker in Garstang, Bruce Crowther, and his colleagues convinced fellow residents to make Garstang the world’s first certified ‘Fair Trade Town’. Since then, many towns and cities around the globe have followed their example and have become certified by the Fairtrade Foundation for agreeing to promote the use of Fair Trade products in their areas. In 2004 Lancaster, Morecambe and surrounding areas became officially recognised by the Fairtrade Foundation as a ‘Fair Trade District’. Meanwhile, Garstang has partnered with two other Fair Trade Towns – New Koforidua in Ghana and Media, Pennsylvania in the USA – to create a ‘Fair Trade Triangle’ that links three regions where previously the Triangle Trade had operated.

In 1994 a Quaker in Garstang, Bruce Crowther, and his colleagues convinced fellow residents to make Garstang the world's first certified 'Fair Trade Town'.

- [1] “Negro Slavery,” Lancaster Gazette and General Advertiser, for Lancashire, Westmoreland, &c., Issue 1623, July 21, 1832; p.3.

- [2] This letter and accompanying documents can be found in Papers relating to Friends’ anti-slavery campaign, FRL 2/1/33/153, Lancashire Archives, Preston.

- The estimated value of the Lancaster and Preston Quakers’ donation is based on information from the National Archives’ currency converter.

- [3] “Notices,” The Anti-Slavery Reporter [British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Reporter], Issue 6.9, April 30, 1845; p.80.

- [4] “An Appeal to the Women of Great Britain on the Disuse of the Produce of Slave Labour” The British Friend Volume 6, 7th Month, 1848; p.174.

- [5] “American Slavery – The Free Labour Movement” The Anti-Slavery Reporter, Issue 5.58, October 1850; p.160.